The ancient and famous Andalusian breed

written in Spanish by Fabian Corral Burbano de LaraThe South American breeds originate from the old Andalusian horse brought by the Spanish conquerors. A breed of great strength and hardiness, they quickly adapted to the harsh conditions of the new geography and since the beginning of the Conquest, were determinant in the war against the ‘naturals’. The colonization and formation of new nations and cultures would not have been possible without the use of these horses. The Criollo horse made the Americas possible.

Garcilaso de la Vega, the Peruvian writer -descendant of a Spanish Captain and an Inca princess- wrote: "My land was conquered by horse... The breeds of horses of all kingdoms and provinces of the Indies discovered by the Spanish after 1492 and until the present, descend from Spanish mares and horses, namely from Andalusia." A few years after the discovery of the Americas, the horse farms established in la Hispaniola, Cuba and Central America provided excellent animals that were used in the conquest war of the Aztec Empire. Also for the ‘incursions’ the Spanish adventurers made to Peru, Quito, Chile, Tucuman, and what would later become the Viceroyalty of La Plata and other South American lands.

The ancient Andalusian horse – nowadays and extinct breed- didn’t have Arabic origins. The studs that existed in the days of the conquest, in Cordoba, Seville and Jerez de la Frontera, had its origins in the Barb horses, brought centuries earlier by Moorish invaders. These horses, mixed with the native ones originated the famed Spanish horse, then known as ‘horse rider’ referring to the warriors of the Moorish tribe xeneties, who were eminent breeders and warriors. They expanded in the Castilian kingdoms and implemented, sports and practices known as the ‘school of the rider’, which gave way to the traditions, styles, methods for breaking and riding that still pervade among gauchos, barges, huasos, chagras, and so on.

The Andalusian horse from the Sixteenth Century -famous throughout Europe for his strength, and airs of arrogance- was good for war and the rough sports of that era, according to the Argentine specialist Angel Cabrera. "... a rather smaller type, perfectly mesomorph, usually a little close to land, with wide box, wide chest, muscular neck and rather short, round, sloping rump and low tail. These last two features come from the Barb breed. "His height was around to 1.47 m to the cross, a characteristic that was then called the ‘Spanish sign’ or the ‘seven quarters.’

Painting : A White horse, Vélasquez

The Andalusian horses of those times were not, strictly speaking, like the current Spanish purebred. The latter are the result of further mixes made from Andalusian horses. As early as the Seventeenth Century, the Royal stud of Aranjuez was mixed with Frisian and Danish breeds. The Bourbons introduced Neapolitan horses. The Napoleonic invasion further changed the original Spanish bloodstock. However, the Criollo horses -Argentineans American, Chilean, Peruvian Paso, etc.- arrived to the Indies before systematic crossbreedings took place, thus retaining, in general, the features of the Spanish breeds of the early Sixteenth Century.

The Criollo Breed is born

The horses of the conquerors gave rise to different types of South American horses. I turn now to the so-called ‘Criollo breed’ whose habitat extends from southern Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina and Chile. Noting however, that they share bloodlines with the Peruvian Paso, Venezuelan Llanero and those inhabiting Ecuadorian lands.“From those stallions and mares, exposed to different weathers, fed with different pastures, employed on different tasks, the descendent horses got adapted to the geographies, treacherous diseases and risks of the environment. In turn, somatic morphologies and physiological gifts managed by the crosses and selections imposed by men appeared, either within the wild herds or the cavalries. These set of conditions gave way to the various types of American Criollo horses. Llaneros and mesteños, horses ridden by Chilean huasos and Mexican charros, herds of a hair of the River Plate gauchos... constructed the reality and legend of the Criollo horse."

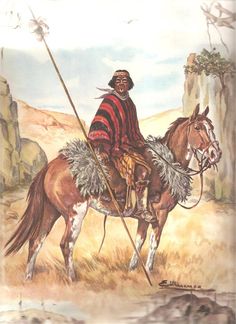

During Colonial times, the Criollo horse affirmed its characteristics in the Americas; it became part of the history of those lands, it contributed to the construction of the new countries. The Criollo horse generated a culture around himself, a new venue for human expression -charros, chagras, gauchos, huasos and llaneros-. It helped indigenous groups to become riders too -Redskins, Araucanos, Pampas and Tehuelches- to prolong their freedom with help of these animals, which joined their collective life, becoming their weapon, vehicle, food and passion. Different implements, costumes, ponchos, songs, customs and styles were born around the Criollos.

Pintura: "Fui puestero en el Tandil" - Carlos Montefusco

In Chile, the needs brought by warfare, livestock and transport generated early its characteristic equestrian culture. By the mid-Seventeenth Century, had already breeding ‘arm’ horses –meaning ambling horses of great character and sharpness- on the estates of the Central Valley. Good for ostentation rides and parades; for ambling gaits, for travel; also for trot and canter for combat and rodeo -the national sport. The Chilean horses were famous for their beauty, spur and docility since early Colonial times. The huasos are the human expression of that marvelous love of Criollo horse is kept in Chile.

Argentina, Uruguay and southern Brazil are the South American regions where the Criollo horse proliferated more widely. Some of the animals used for warfare, brought in 1535 by Don Pedro de Mendoza, the conqueror of La Plata, were set free after Buenos Aires was destroyed and burned by indigenous tribes. Thanks to the conditions of the pampas, that little lot of horses adapted and reproduced portentously. The descendants formed herds of hundreds of thousands of wild horses –known as baguales- which were regarded in amazement by the Spanish conquistador Garay when he arrived to those territories in 1580. Those horses crossed bloodlines with the ones brought by Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca for the conquest of Paraguay and were subsequently introduced in Uruguay and southern Brazil. All those horses had the the same Andalusian origin, although some came from Charcas and Peru.

The colonial life and stormy history of the nascent Argentina revolved around cattle and horses. Sales of leather, beef and tallow sustained the country. The cattle ranches were handled using horses until the introduction of barbed wire. Pampa ranchers also raised large batches of mules that sold to Peru for working in the mines of Potosi. The route of the mules, from the humid pampas to Upper Peru, was described by Carrio de La Bandera, in a classic book about colonial travel and discoveries of the late Seventeenth Century called ‘The Blind Walkers Lazarillo’. The gauchos emerged as the most complete expression of man on horseback.

Painting: La ultima Lomada, by Aldo Chiappe https://www.facebook.com/aldo.chiappe

Both Gauchos and soldiers made history on the back of Criollo horses. The indigenous from the pampas became the best riders in the world and so did ‘war raid’ that ended only at the end of the Eighteenth Century. War leaders such as Juan Manuel de Rosas, Facundo Quiroga and José Gervasio Artigas were primarily horsemen.

"Indio de Lanza" Junio 1879 - Eleodoro Marenco

Decline and new rise of the Criollo

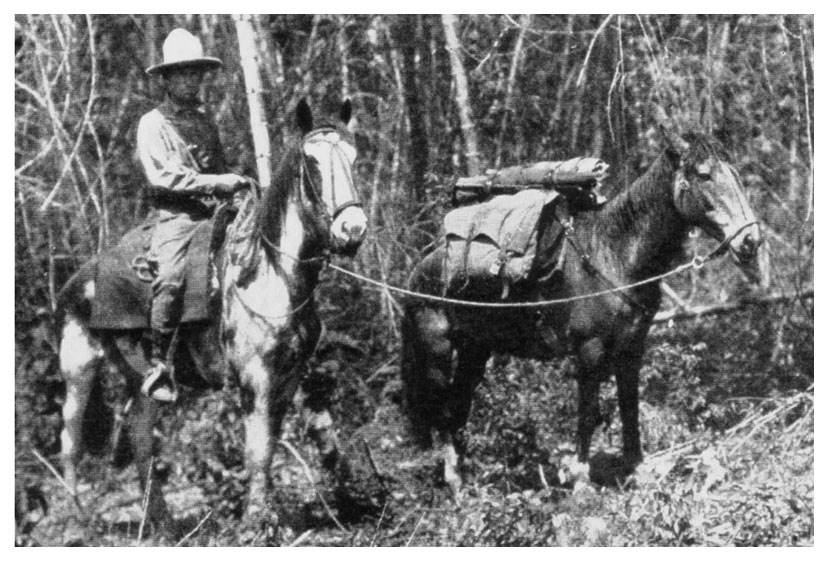

Argentina was a country populated by native horses descendent from the Andalusian breed. However, from the mid-Nineteenth Century, British and Percherons horses were introduced to the country. The indiscriminate crossbreeding spread in search of higher horses. However they were not very functional for war, livestock or traveling. By the early Twentieth Century in some areas of the province of Buenos Aires it stopped being usual to find pure Criollos.Some ranchers, including the Argentine zootechnist Don Emilio Solanet, noticed such a serious situation and undertook the task of restoring the purity of the breed. Solanet found pure Criollos in the distant lands of Chubut. He bought a number of mares and stallions from an indigenous leader and led them on a historical journey of 1800 miles to his farm ‘El Cardal’ in the province of Buenos Aires. From that batch of horses, carefully preserved by isolation and the zeal of the indigenous tribes, the pure Criollos resurfaced. From such an effort the breed registry was born and its traits asserted.

Among the Criollo horses acquired by Solanet in Chubut, there were two mature ones ‘Gato’ and ‘Mancha’. They did, between 1925 and 1928 the historic raid Buenos Aires-New York that covered 22,500 kilometers by mountains, desert and jungle. This is one of the most demanding functional testing distance that positioned the Criollo breed as the best on longest routes. Both horses returned to ‘El Cardal’ by boat, and died at thirty years of age. In 1925, Mr. Abelardo Piovano tested the strenght and endurance of a single specimen ‘Lunarejo Cardal’ between Buenos Aires and Mendoza. The distance was 1380 kilometers in 15 days, carrying 96 kilos. Currently, Argentine (…).

Breed standard

The breed standard adopted by associations of Criollo breeders in Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay and Chile is: mesomorph, average height between 1.40 and 1.50 m hands. Chest 1.70 to 1.86, near land. Broad-based head and fine vertex. Medium lenght, robust neck, muscular and slightly prominent cross. Wide and square rump Good bones, remarkably broad chest, big muscular structure. Usually trot and gallop, although some pace, durable and adaptable to very stringent conditions.Predominant colors are chestnuts, dun, auburn, roan and tobiano layers. Features are the dark stripe along the spine, also known as ‘mule stripe’, and the cebraduras or zebra stripes on the legs, also known in Ecuador as mishimaqui or cat hand.

Picture: Argentinian Criollo stallion owned by the author of this article.

Bibliography

Cabrera, Ángel, Caballos de América; Ponce de León y Zorrilla, Criollos de América; Salas, Alberto Mario, Las Armas de la Conquista.; Morales Padrón, Francisco, Historia del Descubrimiento y Conquista de América; Dowdall, Carlos, El Caballo del País; Solanet, Emilio, Raza Criolla; Solanet, Emilio, Pelajes Criollos; Sánenz, Justo, Equitación GauchaAuthor: Article written by Fabian Corral Burbano de Lara, Lawyer and Doctor in Law, member of the Ecuadorian Academy of the Language since 2013, a friend passionate about the Criolla Culture and Criollo Horses, author of the book: La Historia desde las Anecdotas, Jinetes y Caballos, Aperos y Caminos, Tramaediciones 2014.

Special acknowledgement to Marcela Priego Pérez who translated this article to English.